- Simon Flowers speaks of catalyzing finance for the energy transition in developing countries

Financing any aspect of the energy transition is tough. Funding the developing world’s transition, a topic central to the first Global Energy Transition Congress in Milan recently, is one of the most complex challenges that must be overcome in tackling climate change.

Ed Crooks, Vice Chair Americas, and I joined a full and frank discussion there with guests including the Right Honourable Tony Blair, Secretary John Kerry, Ambassador Patricia Espinosa (formerly of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change), ministers of state from multiple developing countries and industry leaders from energy and finance. We picked out five main themes.

First, there is widespread recognition that the transition in the developing world depends on foreign investment

But it should also be seen as an opportunity for investors. Many developing economies have the natural resources – solar, wind, hydro, geothermal – to build a low-carbon energy system. But they also desperately need access to substantial external sources of low-cost capital to develop them.

There’s a view among developing countries that too much is expected of them – to push on with the energy transition and reduce emissions, even as they strive towards prosperity. The primary responsibility should instead lie with the wealthy G20 countries that own almost 90% of global GDP, are responsible for 90% of emissions and aren’t doing enough, China included. If they were to get on track for net zero it would both solve the climate problem and deliver the viable and affordable low-carbon technologies that the developing world could utilize.

Second, money has begun to flow, but at a miserly rate

The developed world has finally come good on its commitment at COP15 in 2009 to mobilize US$100 billion a year for developing economies to tackle climate change. That target was achieved in 2022 and probably repeated in 2023, the 13-year time-lapse illustrating how difficult it is to turn climate aspirations into actions. Even with the target reached, developing countries are frustrated that they are seeing none of it yet.

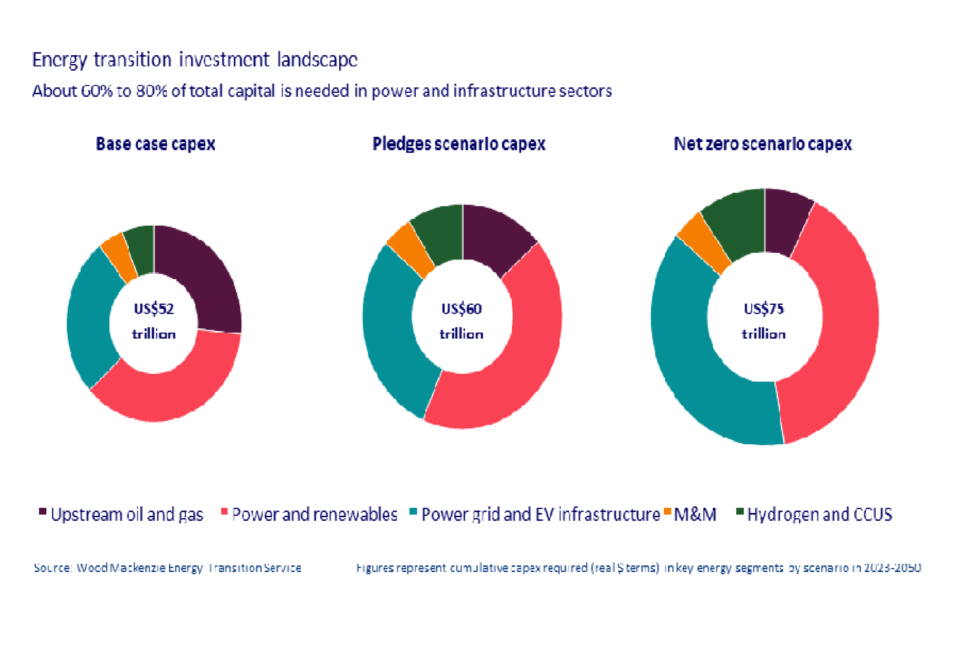

In the meantime, the financing ask is ballooning. Current estimates suggest that upwards of US$4 trillion a year is needed to tackle adaptation and mitigation in the developing world. This at a time of record levels of government indebtedness in much of the developed world.

Third, the environment for investment in the energy transition is challenging everywhere

Renewables build-out is happening. But the anticipated scaling-up of low-carbon technologies such as hydrogen and CCUS is not taking off at the pace expected, even where the policy framework and subsidies are supportive, as in Europe, the UK and the US.

It’s exponentially tougher for developing economies. A perceived lack of political stability and limited policy frameworks to support low-carbon investment add to the risks for investors. We estimate the cost of debt in non-OECD countries averages 12% to 14%, three times that in OECD countries.

Fourth, developing economies need help accessing low-cost finance

Some of it has to be self-help. The private sector won’t invest in low-carbon projects that require capital to be committed for decades without the basics in place to help underpin economic returns. Countries need political stability, transparent governance, legal and commercial frameworks, policy signals and sound energy market rules. Offtake arrangements – say, for a renewable hydrogen project with an investment-grade user, such as a utility or industrial consumer – can be critical to whether a project can secure financing.

But developing countries often find it difficult to know who to talk to, or how to present their case to maximize their chances of securing financing. Roadmaps to help guide them through the maze of international institutions, government programmes and private sector lenders could make a big difference.

Fifth, where will the finance come from?

Carbon markets are widely seen as a silver bullet. In their simplest form, they tax emitters and incentivize investment in low-carbon systems. But a global carbon market won’t happen until major emitters such as the US, China and India implement schemes in their home markets at prices high enough to drive low-carbon investment. That seems a long way off.

Credit is due to philanthropists, but the sums Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos and others are mobilizing are modest in the grand scheme of things.

The International Monetary Fund maintains the special drawing rights that could be used to finance climate mitigation and adaptation. The IMF could use the same approach as during the peak of the Covid pandemic, when it released US$650 billion to developing countries.

The big money, though, lies in private hands – the ‘wall of capital’ held by companies and institutions looking to invest in attractive low-carbon opportunities across the developing world. Crowding in that private capital depends on clear policy signals that have yet to materialize from developed world governments, including the US, EU, UK, Japan and others.

A proposal in Milan for a ‘Global Climate Bank’ resonated. Perhaps the time has arrived for a global body to play that essential, as-yet unfilled role: coordinating governments, private companies and institutions and channelling finance at the scale and pace required for the developing world’s energy transition.