Africa’s energy statistics make for a disappointing read. As world leaders meet for the COP29 talks, some 600 million Africans still have no access to electricity and per capita energy consumption remains the lowest globally. This situation is even more absurd given the continent’s massive untapped oil and gas resources and staggering potential for low-carbon energy.

Gavin Thompson, Vice Chair EMEA, was at the Africa Energy Week in Cape Town and had four major takeaways from the event.

Africa’s priority must be developing its bountiful oil and gas resources

Tackling energy poverty means Africa taking back control of its own energy future. Across Africa, the frustration is palpable at the slow pace of growth in oil and gas production, hurdles to securing finance and projects hamstrung by concerns over carbon emissions.

It’s not hard to see why. Africa accounts for only 3% of global annual emissions, with sub-Saharan Africa emitting just 1% of the total when we exclude South Africa. It’s hardly surprising that many African countries are adamant that they prioritize developing fossil fuel resources to drive economic prosperity and deliver affordable energy to their people.

No place on earth comprehends the negative impact of climate change better than Africa. But Africa’s emissions aren’t the root of the problem. In Wood Mackenzie’s base case in the Energy Transition Outlook (ETO), Africa’s contribution to global emissions climbs to just 6% by 2050, even with rising oil and gas demand. Little wonder then that Africans are increasingly vocal about the lack of progress with new project development.

Natural gas must play a greater role at home

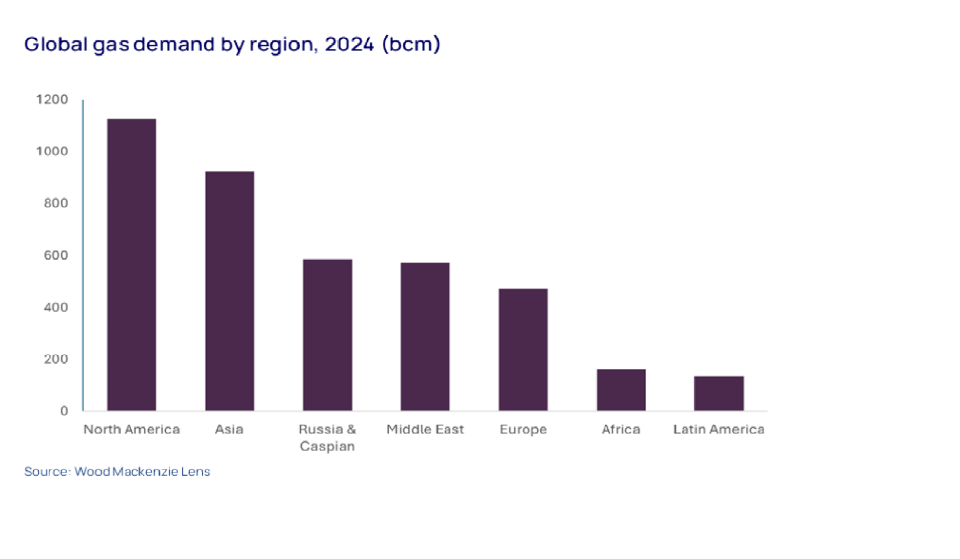

Africa is already a major LNG exporter, contributing almost 10% of the global supply. But Africa itself consumes only 4% of the world’s gas supply with the lowest gas consumption per capita globally at less than one-quarter of the global average.

Whether Africa produces its gas for export or develops domestic markets isn’t a binary option. Accelerated LNG development across West Africa and Mozambique not only provides valuable export revenues but can also anchor local demand. To deliver on this, issues around affordability, infrastructure and the lack of credit-worthy offtakers must be addressed.

Building a low-carbon energy future

In addition to oil and gas reserves, many African countries boast enormous untapped solar and wind resources and significant hydro and carbon capture potential. These resources provide Africa with an enviable opportunity to build a low-carbon future around renewables and hydrogen while simultaneously decarbonising fossil fuel supply.

Electrification is critical. With only 49% of sub-Saharan Africa’s population having access to electricity, developing new capacity is the bedrock of development. Demand doubles by 2050 in the ETO and grows four-fold in our 1. 5 degrees Centigrade net zero scenario.

Many African countries currently operate more distributed diesel capacity than on-grid capacity. Developing major infrastructure will be tough, but distributed solar can replace diesel. With the gap between diesel and solar costs widening, solar is an increasingly competitive alternative, potentially displacing 30 to 40 GW of oil-fired capacity across Africa by 2050.

Africa’s huge CCUS and low-carbon hydrogen opportunities are building momentum. Countries in Northern Africa are pushing green hydrogen projects to target Europe, taking advantage of low-cost renewables and proximity to markets. Blue hydrogen hubs are proposed in Nigeria, Mauritania, Mozambique and Senegal.

Financing is the final part of the puzzle

If financing any aspect of energy is tough, funding African projects is one of the most complex challenges.

Developing Africa’s energy needs on its own terms isn’t at odds with foreign investment. It’s dependent on it. With huge undeveloped oil and gas reserves and the natural resources to build a low-carbon energy system, Africa desperately needs substantial external sources of low-cost finance – a major challenge when capital costs for African projects are often up to three times those in other countries.

The developed world may finally have come good on its 2009 commitment to mobilize US$100 billion a year for developing economies to tackle climate change, but African countries are frustrated at the pace of access to funds. After more than a decade since the commitment was announced, it was only achieved for the first time in 2023. Given the agreement’s vintage, we estimate the requirement now to be closer to US$500 to 800 billion a year.

State-backed finance is only a part of the story: Africa must attract big money from the private sector to reach its full potential. Herein lies the problem. For African upstream projects already stalling over access and cost of capital, securing additional finance to scale up CCUS means more ESG hoops to jump through. As indigenous NOCs and local E&Ps increasingly fill the gap left by Big Oil’s continued divestment of assets across Africa, raising finance isn’t getting any easier. Local options, including the African Energy Bank which will begin operations in 2025, are available but will need to be mostly funded by African member countries and partners.

It’s a similar story with low-carbon opportunities. African countries must demonstrate a favourable investment environment, ensure political stability and develop the necessary infrastructure to succeed. It is unsurprising that, to date, only 2.5 Mtpa out of Africa’s 22 Mtpa of proposed hydrogen projects across North and West Africa are under development. Project and political risks, alongside a lack of offtake arrangements with investment-grade buyers, too often snarl up financing.

Financing Africa’s energy needs is simultaneously one of the world’s great investment opportunities and among its most formidable challenges. As the global competition for energy sector capital continues to rise, Africa’s voice must be heard.

Source: Wood Mackenzie