Simon Flowers Wrote,

- It’s the ‘drop-in’ fuel that could help decarbonise gas supply

Investment in the nascent biomethane sector, also known as renewable natural gas (RNG), is picking up, including large-scale M&A as Big Oil and manufacturers build positions. I asked Kateryna Filippenko, who leads our new Biomethane/RNG service, how she sees the market developing.

What is biomethane?

It’s derived from upgraded biogas, which is mostly produced from organic feedstock such as food waste, sewage and landfill, agricultural crops, manures and residue. Virtually identical to fossil gas, biomethane can be “dropped in” to the gas grid and used in the same applications. It’s considered a low-carbon source on a net lifecycle basis. Carbon emitted on combustion matches that absorbed in growing the plant feedstock – no new carbon is brought into the global system. Biomethane produced from waste avoids methane emissions that would’ve occurred if it were to degrade naturally.

Where are the growth markets?

North America, where federal, state and provincial government incentives have boosted market development. We now track close to 500 active biomethane projects across the US and Canada, up from 162 sites just four years ago.

Europe’s decarbonisation targets and diversification away from Russian gas imports have also sparked rapid growth, albeit from a small base – biomethane capacity jumped 35% in 2023. However, in our view, a lack of clear policy support puts the EU’s ambitious target of five-fold growth to 35 bcm a year by 2030 in doubt. Brazil, Australia, Malaysia, China, India and Indonesia all have nascent industries, too, based on agricultural feedstock.

Sector-wise, marine bunkering has growth potential as regulations on shipping fuels tighten. Repsol and Gasum are among the companies testing the waters with a view to supplying bio-LNG for ships.

How big of a role can it play?

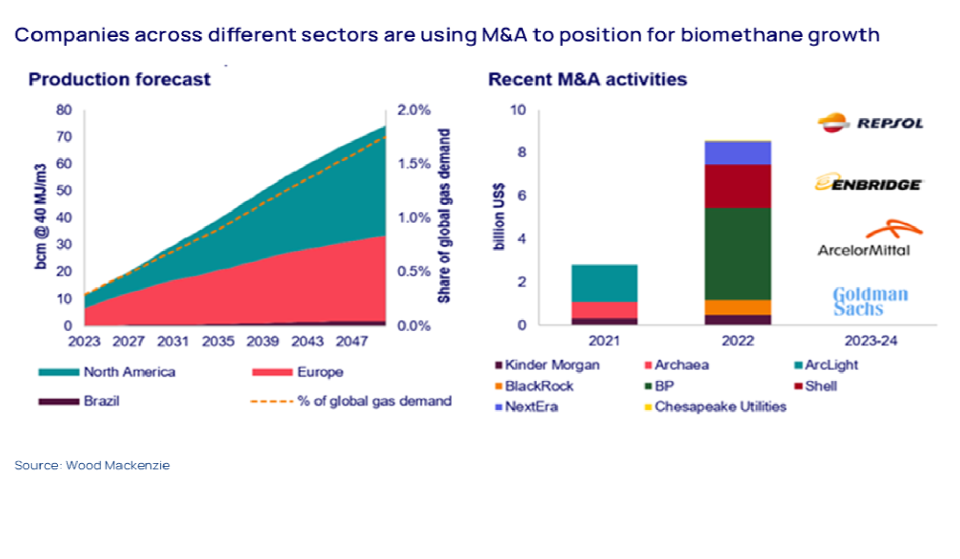

A small but important one in global decarbonisation. We estimate that by 2050, biomethane capacity will grow sevenfold to 74 bcm, supplying around 2% of annual global gas demand and equivalent to almost 10% of global LNG demand. It will be more important in some markets than others – European biomethane production in 2050, for example, could exceed North Sea gas output.

Moreover, our projections for biomethane could prove conservative. In the US, current production from landfills – 70% of the national biomethane supply – taps only about 10% of the 40 bcm annual resource potential. That figure will grow further and excludes sources such as animal manure, food waste and wastewater treatment. Europe’s resource potential (1) could be 150 bcm by 2050 – theoretically sufficient to cover 100% of the bloc’s 2050 gas demand. Brazil’s agricultural feedstock resources, meanwhile, could yield up to 44 bcm (2).

Feedstock for biomethane is almost ubiquitous, opening up the potential for growth in any developed or developing market.

Who is positioning in biomethane?

Companies from multiple industries are looking at the opportunity from different angles. Big manufacturers with on-site gas demand see biomethane as a way to manage their own waste, lower emissions and cover part of their energy needs.

Likewise, the oil Majors can readily integrate biomethane into their gas value chains, although there are different strategic approaches. TotalEnergies is primarily investing organically, others have made sizeable acquisitions – BP with its US$4 billion purchase of Archaea Energy, Shell with Nature Energy, both in 2022. For Big Oil, though, biomethane will remain niche with current targets a fraction of their fossil gas production.

Biomethane remains a highly fragmented market, and one ripe for consolidation, with many small players across landfill, agriculture and animal manure feedstock. We expect continuous M&A activity as the industry grows.

The technology isn’t new, so why hasn’t biomethane scaled up?

A lack of transparent, clear and coordinated policies and regulations is one of its major growth constraints. Biomethane sits at the intersection of multiple sectors – energy, waste, agriculture and emissions management – and tends to fall between the regulatory cracks. Regulatory rules for infrastructure access and international biomethane trade are patchy.

Cost is another. Pre-tax breakevens for US landfill gas range from US$4/mmbtu to US$35/mmbtu, depending on plant size, proximity to the grid, operational efficiency and upgrader technology. Costs for other feedstocks are typically higher still. With Henry Hub likely to average below US$4/mmbtu through this decade, the commercial proposition depends heavily on government incentives and the value of environmental attributes.

Incentives for producers can come in the form of direct subsidies or tax credits, while volume mandates lead consumers to assign value to the fuel’s environmental attributes through biomethane certificates and guarantees of origin. Monetizing by-products from biomethane production – such as biogenic CO2 and digestate – can help boost value further. Assuming subsidies will eventually wind down in many markets, producers need to find innovative ways to create value from biomethane on a sustained basis.

What needs to happen to foster stronger market growth?

Biomethane can be an important and investable part of the decarbonisation puzzle, bridging the gap between fossil fuels and emerging technologies, such as hydrogen or e-fuels. Future success depends on two things. First, strong policy support at local, country and regional levels to ensure consistency of regulation and incentives – including creating conditions for trading of biomethane certificates and guarantees of origin. Second, creative business approaches, development of a voluntary market and cross-sectoral coordination.

Source: Woodmac