By Ejekwu Chidiebere

India is set to become a major player in the global energy markets with a unique growth path, featuring lower energy intensity, a diverse energy mix and increased commodity imports, reveals WoodMac’s latest Horizons report.

The report, “Eye on the tiger: How higher Indian economic growth could impact global energy markets”, highlights that, unlike China’s energy-intensive boom in the early 2000s, India’s growth is expected to be more balanced, with a focus on high-value manufacturing and renewable energy.

“India’s growth story shares similarities with China’s rapid expansion, but crucial differences set it apart,” says Yanting Zhou, principal economist at Woods. “While energy demand will surge, India’s industrial sector is less energy-intensive, and the country is better positioned to adopt efficient, low-carbon technologies compared to China in the 2000s.”

The trajectory which Woods considers as “unique” could accelerate, WoodMac says, India’s transition to a low-carbon economy, potentially enabling the nation to achieve its net-zero emissions goal ahead of the 2070 target.

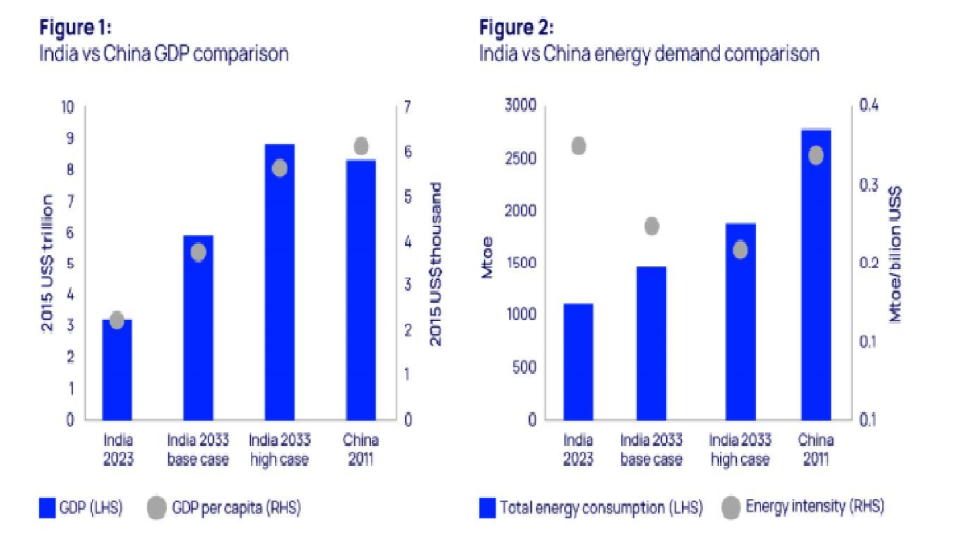

India’s high-growth scenario by 2033 as Woods’ report highlighted suggests that the country’s economy will reach just under US$9 trillion, nearly triple from US$3.2 trillion by 2033, with coal demand growth to nearly double to 2.2 billion tonnes, while oil demand is expected to reach 8.2 million barrels per day, up from 5.6 million barrels per day. Power demand will surge to almost 4,000 TWh, this is with increases in both coal and renewable generation, while the demand for steel will rise 9% annually, reaching 317 million tonnes

Energy Window International has also gathered that India’s growth is also expected to be driven by high-value-added manufacturing, including renewables and advanced batteries, to be supported by government subsidies and technological advancements.

On lower energy intensity, Energy Window International equally gathered that India’s industrial sector currently consumes less energy per unit of GDP than China did in the early 2000s. Thus by 2033, crude steel and cement production in the country is projected to be only about one-third of China’s output in 2011, this is besides an increasing share of renewable energy and the adoption of electric vehicles – the totality which is expected to further lower country’s energy intensity.

While competition for commodities is expected to rise under the high-growth scenario, India’s growing demand may not possibly trigger any significant price surges like the situation during China’s boom of the 2000s, attributed to OPEC+ sufficient spare capacity which accommodated the increasing oil demand from the Indian axis. Consequently, India’s oil demand is projected to increase Brent prices by a relatively modest US$1 to US$3 per barrel.

The additional demand for 10 million tons per annum (Mtpa) of LNG from India WoodMac says, will arise during a period when global gas prices are expected to decline, meanwhile the market WoodMac says, is preparing to absorb more than 200 Mtpa of LNG supply growth, thereby accounting for about 50% of current supply, while limiting potential price increases for LNG.

Energy Window International has as well gathered that the country’s thermal coal production could reach 1,800 metric tons (Mt) by 2033 in the high-growth scenario, driven by the need to ensure energy security. However the country will still need to import around 200 Mt from the seaborne markets. Meanwhile the current seaborne thermal coal cost, approximately US$107 per tonne, could rise to US$110 per tonne by 2033.

While CO2 emissions initially rise due to the rapid expansion of coal, India’s high-growth scenario could accelerate low-carbon supply chain development, potentially enabling faster decarbonisation post-2030s.

Roshna Nazar, research analyst, energy transition at Woods, said: “If India can repeat China’s post-2010 strategy of investing in low-carbon supply chains for solar, wind, electric vehicles, and critical minerals, the higher emissions anticipated in the early 2030s will be temporary. This stronger growth could lay the groundwork for faster and more durable decarbonisation to follow.”

Woods noted that energy and natural resources producers were likely to benefit from increased demand, particularly those located in Russia, the Middle East, Australia, Indonesia, and South Africa although investors will need to prioritise securing a first-mover advantage before domestic companies scale up.

Wood Mackenzie estimates that India will need to invest US$600 billion in its power sector over the next decade – indeed a significant investment opportunities for power generation capacity additions, grid improvements, and supply chains according to Woods.

Adding that the Indian government is well-positioned to implement innovative strategies that balance energy security, emissions reduction, and economic growth, all while ensuring affordable energy access. Maintaining that by implementing supportive policies—such as streamlined approval processes, attractive incentives for renewable energy projects, and the promotion of public-private partnerships—India can significantly decrease its reliance on commodity imports after 2035, a shift which could improve the balance of payments, reduce public debt, and boost foreign reserves.

Zhou concluded, “In addition to rising imports, achieving higher growth will require significant investment in domestic energy production, oil refining, steelmaking, and low-carbon supply chains. Just like in China during the 2000s, there are many opportunities to explore.”